James Franklin Jollett was 25 years old when Civil War

was declared to defeat the Southern states’ attempt at independence from the

Union. He had been married to Lucy Ann Shiflett for less than two years, and he

was the father of their 6-month old baby boy Burton Lewis. Maybe that is why he

did not enlist right away as did his older brother John Wesley Jollett.

Yet ironically, ten days after his second child Emma was

born in February 1863, he joined the 46th Regiment of Virginia

Infantry, Company D as a private. When the regiment was formed in 1861, it saw

action particularly in a siege against Charleston, South Carolina. But by 1863,

it had been renamed “Border Guards” and the troops were sent to Albemarle

County, Virginia to build fortifications near Chaffin’s Bluff.

Yet ironically, ten days after his second child Emma was

born in February 1863, he joined the 46th Regiment of Virginia

Infantry, Company D as a private. When the regiment was formed in 1861, it saw

action particularly in a siege against Charleston, South Carolina. But by 1863,

it had been renamed “Border Guards” and the troops were sent to Albemarle

County, Virginia to build fortifications near Chaffin’s Bluff.

As it turns out, a major battle ensued at Chaffin’s Farm

in September 1864. As part of General Ulysses S. Grant’s siege of Petersburg,

this battle forced General Robert E. Lee to shift his resources away from the

Shenandoah Valley, which ultimately benefited the Union’s efforts. The battle

at Chaffin’s Farm cost the lives of over 5000 soldiers.

But not James Franklin Jollett. Why?

He was not there.

According to his service records, Frank Jollett deserted

in July 1863, five months after he enlisted and over a year before the costly

battle.

What the circumstances were that led him to pack up all

his clothes and head back home to Greene County is anyone’s guess. Maybe it was

the fear of “Chaffin’s Farm Disease,” a fever that spread throughout the camp.

Maybe it was concern for his young family. A story told

by his granddaughter Vessie Jollett Steppe suggests James Franklin was just not

tough soldier material. While serving as

a guard delivering prisoners of war by train, he chatted with a prisoner who

spoke of how much he missed his family and how he would give anything to see

them one last time. Sympathizing with his plight, Frank told him he was going

to step outside the train for a smoke. While he was outside, the prisoner

escaped, much to Frank’s delight.

Vessie said that family was everything to her

grandfather. She said, “He would cry when you came to see him and he would cry

again when you left.”

Or maybe because he was never paid, he just left. The

Muster Rolls for January through April show he had not received pay.

Actually, desertion on both sides was very common during

those years of the Civil War, especially among farmers who needed to go home to

plant or to harvest. So maybe that was why he left.

|

| from Descriptive List and Account of Franklin Jollett, Deserter |

According to the official records, however, he never returned and was officially dropped from the rolls in December 1863.

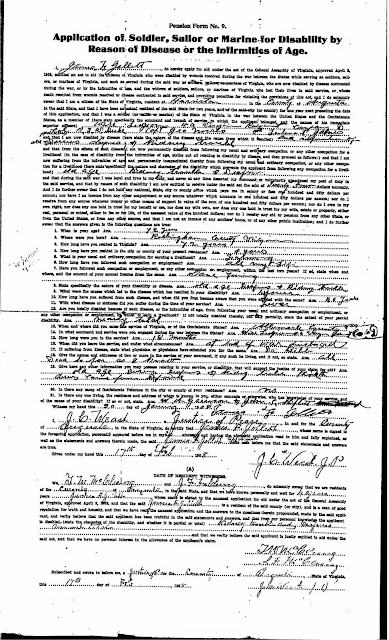

That information conflicts with James Franklin’s

testimony on his pension application. He claimed to have served eighteen months

and left service at the end of the war. (Admittedly, it is possible that he

simply lied in order to get that much-needed pension.)

To justify his request for a pension, James Franklin

cited not just old age but also his near-deafness and kidney trouble, blaming

fever endured during the war. The fever might very well have been “Chaffin’s

Farm Disease.” The term is not associated with any known disease today but

reflects the location of a particular outbreak. Most field hospitals were known

for “fevers” and diarrhea-like ailments stemming from the unsanitary conditions

made even worse by lack of understanding of how disease spread.

Apparently James Franklin’s record as a deserter had no

bearing on his application as it was approved. On April 18, 1908, he was awarded

a monthly pension of $24. When he died in 1930, his widow Eliza Jane applied

for a widow’s pension and likewise was granted approval for $10 monthly.

Wendy

© 2016, Wendy Mathias.

All rights reserved.

War is horrible - I'm glad he missed that horrible camp fever.

ReplyDeleteMe too - of course, that's assuming he really did avoid getting it.

DeleteMakes you wonder if desertion was common too because people thought it would be a quick fought war and they could return in time for spring planting, etc. Glad he was able to get the pension; anyone who served anytime in a war I think should be entitled to one, no matter how short of time the service might have been.

ReplyDeletebetty

Being granted a pension despite deserting is confusing to me, especially since the application clearly states that the applicant had to remain faithful and true to the cause, never deserting his post. So did he lie? Did no one at the pension board check? Did the government just say, Oh well, you're forgiven?

DeleteI'm glad he received a pension but geez, those pensions were pittance! My Civil War guy received a similar amount.

ReplyDeleteYes, $24 doesn't sound like much, but according to the online inflation calculator, it equates to over $630 today.

DeleteWhat an interesting story. And I agree with Debi, those pensions were pittance. Thanks for sharing.

ReplyDeleteI found a website that claims in 1908, eggs were 14 cents a dozen, coffee was 15 cents a pound and sugar was 4 cents. The average annual salary was between $200-$400. That makes the $24 pension look pretty good.

DeleteSo many with CW soldiers have similar stories in their families. I know I do. It was an awful experience for which few of the farm boys were really prepared. I am glad he got the pension though, although pitifully small.

ReplyDeleteI agree. Fulfilling one's patriotic duty was surely expected of every able bodied boy and man despite lack of training and supplies. It had to be hard on the women left behind to keep a farm going.

Delete