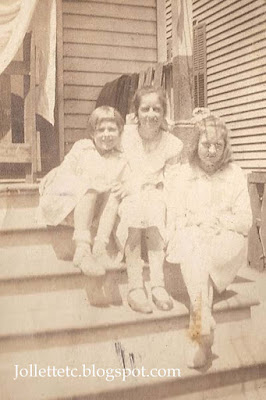

This week’s Sepia Saturday photo is of sisters and their

dogs on the steps of a mansion. About 1935, someone snapped a picture of my

mother and her brother and their dog Fritz on the front steps of someone’s home

which was anything but a mansion. The smiling gentleman was their grandfather’s

brother known among family as “Uncle Renza.”

|

| "Uncle Renza" (1871-1947) my mother Mary Eleanor Davis and her brother Orvin Jr. and of course, Fritz |

Apparently Uncle Renza was an object of pity. He seemed

to be poor. My mother thought maybe he was divorced. He would show up and then

disappear. But those are the recollections of a child. Just what was Uncle

Renza’s story?

He was born Lorenza Ridell McKinley Davis in 1871, the

thirteenth of fifteen children of Mitchell and Martha Willson Davis of Rockingham

County, Virginia. He obtained a sixth grade education, which was the typical

length of education in rural parts of the state at that time. In August 1892,

he married Chillis/Chelie Ann Shiflett of Greene County.

By 1900, Lorenza and Chelie or Anne or Anna, whatever she

went by, were the parents of four children under the age of six. As was typical

of women of the time, Anne took care of the household in their rented home in

Augusta County while her husband worked as a farm laborer, likely on someone

else’s farm.

|

| Company houses at the logging camp near Boyer photo courtesy Cass Scenic Railroad State Park cassrailroad.com |

In the census record for that year, Lorenza and Anne

could boast that all six of six children were still living. But something must

have happened to the family after 1910. Lorenza and Anne are nowhere to be

found in either the 1920 or 1930 census. None of the usual creative spellings

and combinations have produced a hit. Maybe it was true – maybe they divorced

and maybe Anne remarried. Nevertheless, that does not explain Lorenza’s disappearance.

Most of their children did not show up in 1920 or 1930

either. Those that did were married but apparently did not take their parents

in.

Incorrect information on the children’s later marriage

and death records led me to search using the names “Lorenzo McKinley” and

“Alonzo Davis.” Still nothing.

|

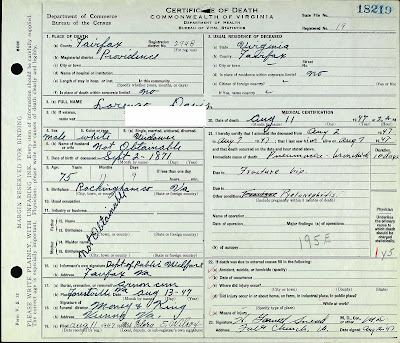

| Death Certificate for Chelie Anne Shiflett Davis |

Virginia death records recently released on Ancestry.com provided a few answers while sparking new questions. Anne’s whereabouts were confirmed: at least by 1939 and in failing health, she moved to Covington, Virginia, likely near, if not with, her daughter Bessie Weiford who was the informant on Anne’s death certificate. The answer to the question of whether she and Uncle Renza were divorced seems to be “No.”

However, in the 1940 census, Uncle Renza claimed he was

Single. Yet at his death in 1947, he was a widower according to his death

certificate.

For a few years at least, Uncle Renza seemed to be getting

by. He owned his home, but it was valued at only $100 while his neighbors’

homes were valued between $1200 and $6000. At age 69, he was still employed - as

a laborer for a private family. That probably translates as “handyman.” He was

already past the age of normal working years, so there is no telling how much

longer he was able to work.

As meager as Uncle Renza’s life seems to have been, his

circumstances must have taken a grim turn. The informant at his death was not

one of his children, not a sister or brother, not even a family friend. It was the Department of Public Welfare in

Fairfax, Virginia.

Whether he had been a long-time recipient of public assistance or had merely fallen on hard times in his declining years is not known. At any rate, my mother’s recollections of a “poor uncle” must have been right.

|

| Death Certificate for Lorenza Ridell McKinley Davis |

Whether he had been a long-time recipient of public assistance or had merely fallen on hard times in his declining years is not known. At any rate, my mother’s recollections of a “poor uncle” must have been right.

Why don’t you and your sister take the dog for a walk to

the Sepia Saturday mansion?

© 2015, Wendy Mathias.

All rights reserved.